STEIN & CO

by William Shakespeare

AN EDINBURGH INTERNATIONAL FESTIVAL PRODUCTION

in association with the Royal Shakespeare Company

Aeneas Simon Armstrong

Hector Richard Clothier

Calchas Arthur Cox

Nestor John Franklyn-Robbins

Agamemnon Ian Hogg

Thersites Ian Hughes

Pandarus Paul Jesson

Menelaus John Kane

Patroclus Oliver Kieran-Jones

Ajax Julian Lewis Jones

Paris Adam Levy

Margarelon Roger May

Cassandra Kate Miles

Andromache Charlotte Moore

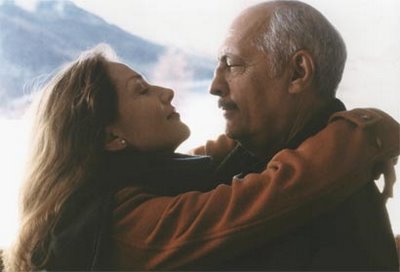

Troilus Henry Pettigrew

Helen Rachel Pickup

Achilles Vincent Regan

Cressida Annabel Scholey

Priam Jeffry Wickham

Diomedes Richard Wills-Cotton

Ulysses David Yelland

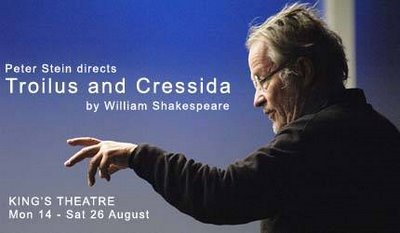

Director Peter Stein

Set Designer Ferdinand Wögerbauer

Costume Designer Anna Maria Heinreich

Composer Arturo Annecchino

Sound Ferdinando Nicci

Fight director Malcolm Ranson

Camped outside the gates of the city, dirty and weary Greek warriors question the endless war as their hero Achilles withdraws and refuses to fight. In the besieged and claustrophobic city of Troy, disillusionment and the breaking of public oaths takes its toll.

Containing coarse and crude comedy as well as high tragedy this is an excoriating exposé of politics and expediency as well as an affecting portrayal of sex and war.

In times of conflict this play has always had a particular resonance, highlighting the gulf between lofty ideals and bleak reality.

Brain grease is the word for German with bard attitude

Interview with Peter Stein by SARAH JONES

Ii is the end of a hot and sultry day in southwest London. Above a crowded high street in an old municipal building, German director Peter Stein and his 33-strong group of actors are slogging through the final fight scenes of Shakespeare’s epic Troilus and Cressida, a joint production between the Royal Shakespeare Company and the International Festival which opens the theatre programme next week.

There is debris everywhere – a pile of plastic swords, assorted junk and discarded clothes scattered about. Stein looks irritable. His Troilus - former Traverse barman Henry Pettigrew making his professional debut - is drenched in sweat in the stifling heat of the rehearsal room, clearly exhausted. »You’re sitting in my chair,« Stein says, staking his claim rather bullishly to the chair I have just been ushered to sit in. Troilus rolls his eyes in sympathy.

Stein is a giant of European theatre. In the Seventies, he co-founded the Berlin Schaubühne as a co-operative, a radical young company formed by a radical young director who now abhors the successful kind of avant-garde German theatre he helped shape. Directing large-scale classics is what Stein is known for, despite a brief reprieve at last year's EIF when he took on David Harrower’s explosive Blackbird. Stein would do it again in an instant, he says.

Now, at 69, every play is about the text. He takes what is written and excavates it until he understands it. That is particularly important in this production because it is Stein's first production of Shakespeare in the original language. »What I discovered clearly, the first time I have not worked with Shakespeare in translation, is what a fantastic author this guy is,« he says.

The large number of fighting scenes are a requisite part of this play set against the backdrop of the Trojan War. »This is a very particular war. This is not Iraq. In Iraq 99% of the people killed are civilians. Soldiers fly over in planes and drop bombs. In Troilus, it is body to body. And it is special because it is fought for a vagina, a placket, Helen’s needle, as Shakespeare says in the play. There are so many words for it. This is the most pornographic of all Shakespeare's plays,« he adds, pointing out the ›blue‹ commentary beneath the text of his well-thumbed copy of Troilus and Cressida.

»My ambition is to tell the story of this very realistic, terrible love story. Not love for God or mankind, or your husband after 15 years, but love where sex is involved. This love is impossible. The way you do this love stuff is not so different 2,000 years ago from now - it uses more or less the same organs. And men are the same - peacocking, fighting, exaggerating, filled with self-pity. Camaraderie, drinking together, boasting, premature ejaculation. You laugh, but every male is afraid of this. These things, they are eternal, you do not need to modernise this.«

Troilus has been a long time coming for Stein who, after 45 years as a director, has the luxury of choosing his projects. »I decided to do this project in 1968, but I've never had the right moment. Brian McMaster asked if I would like to do a Shakespeare with English actors. I could have proposed Lear or Richard II, but you need an actor who can do it. I do not know an actor who can do it.« Aside, he says, from his wife, who will play Richard in an Italian production Stein will direct in 2007.

»THE PROBLEM, of course, with working in English is that I am German,« says the director in fluent English. »I understand Shakespeare even less than you, I say to my actors: When I understand what you say and you understand what you say, then you can be sure that every idiot in the audience will understand. So I am a kind of filter.«

Stein’s second production at the Edinburgh International Festival this year - the Opera de Lyon production of Tchaikovsky's Mazeppa, is also performed in the original language.

»I do not speak Russian at all. I can decipher it, yes, but sometimes even now I don't know exactly what they are singing on stage. But music is wonderful. It is ›Gehirn schmieren‹ - brain grease! I wanted to be a musician you know; I followed music, especially Tchaikovsky. Where I am perhaps not so bad as a director is where I can use this experience and make an analysis of the dramaturgical structure of text and music, because sometimes in opera the two are in conflict.«

If Mazeppa, with its requirements for vast crowds, horses and guillotining, is about creating an illusion of grandeur, Troilus has but one set conceit - a seven-foot wall which slowly descends backwards to form a steeply raked stage.

»McMaster is the only one, over the years, who has always been honest with me in a dishonest business. For me it is a disaster that Brian McMaster is leaving the Festival. He wooed me from 1982 when he was at Welsh National Opera. I do not think I will work in Edinburgh again. I do not think I will work in Britain again. The new director of the Festival will not ask me.«

The thought throws the great German director back into his morose mood of an hour previously. Stein says he hasn’t talked to many journalists - which isn't quite true - as if the world as he knows is crumbling under his feet. »They don’t care, nobody cares,« he says derisively, walking out onto the street. »Nobody is interested in me.«

Lost in Translation

Interview with Peter Stein by JOYCE McMILLAN

It’s a long way from the picturesque hilltops of Tuscany to the Royal Shakespeare Company’s shabby old rehearsal rooms in Clapham High Street. As the temperature in south London soars to a sweltering 30C, it's a journey the great German director Peter Stein increasingly wishes he hadn’t had to make. »It was so lovely over there at my place,« he says, describing his rambling farmhouse home in Italy, and the rehearsals he has just completed there for his Edinburgh Festival production of Shakespeare’s Troilus and Cressida, which will also form part of this year's RSC Complete Works Festival at Stratford-upon-Avon.

»With all these young actors, on the terrace in the evening … really, we had this feeling of being together as a community, which I love, and I am so grateful to the Edinburgh Festival that it allows me to bring the actors to my home, to work with me there.«

Troilus And Cressida, though, has a huge cast of 33, so after a few weeks in Italy with the principal players, Stein had to resign himself to a final month of work in London and Edinburgh. But there’s a sense - as Stein leads his actors through a passionate extra ten minutes of pre-lunch rehearsal - that it would take more than a few practical inconveniences to diminish his huge enthusiasm for the project in hand.

It’s not that this is Stein’s first production for his friend and colleague Brian McMaster, the Festival’s outgoing director. He has been a regular visitor to Edinburgh since 1993, with a series of great stagings of Shakespeare, Aeschylus, and Chekhov, and many opera productions - including this year’s version of Tchaikovsky’s Mazeppa for the Opera National De Lyon. It’s not even that this is his first chance to create theatre in English. That came in 2003, with his acclaimed Festival production of The Seagull.

But this is the first time, after a career full of ground-breaking Shakespeare productions, that Stein has directed Shakespeare in English, using the playwright's original words. At 69, Stein seems as excited as a boy over the new theatrical landscape opening up in front of him - so much so that once he waves the actors off to lunch, and starts talking about the play, it seems he can hardly stop. Troilus and Cressida, he concedes, is probably the most difficult and enigmatic of all Shakespeare’s plays, a famously bitter and uneasy satire of sexual lust and betrayal, set against the backdrop of the siege of Troy - but it's that complexity of drama that draws him to it.

»This is just why I do theatre. I say, ›Let’s do this play, which is so problematic and puzzling, and then I might understand it.‹ And what I find is that this play is very special, even among Shakespeare’s works. Let’s speak about the end, for example. I don’t know any other Shakespearean play that ends so … desperately. There is no end. In all his other plays, after disasters or comic resolutions, there is the feeling that things can start up again, can go on. But here - no. We have a despairing Troilus, a despairing Cressida, not even a pile of corpses. A pimp tells us that we have the same syphilis that he has, and it’s over. It’s an ending like no other, completely nihilistic.«

»Then there is the disproportion of the title story, because the love story - or sex story - of Troilus and Cressida actually has not many scenes, and the huge, overdeveloped presence of what you would call male idiotic behaviour of all kinds.«

»So I had now the chance to do it for the first time, to analyse Shakespeare in the original language, to try to understand this remarkable play. And I find that in these Shakespeare lines, in English, there is absolutely everything we can use to make theatre out of it.«

»It’s not just the lines, the grammar, the syntax, but the sound. There is this enormous skill in rhetoric, in building up the sense and argument of the words, and a lot of acting possibilities that you just can’t see until you work in the original … And then, when you get into the rehearsal room, out comes the most stunning stuff. So now I think I will have difficulty to go back and direct Shakespeare in translation, because I have seen how much you lose, and how much there is in the original.«

It’s perhaps because of this total fascination with text, and with the infinite acting possibilities hidden in its detail, that Stein is wary of obvious attempts to update Shakespeare’s plays, or to point up their relevance to contemporary politics.

»Directors have a tendency to want to say that war is no good,« he says. » Well, we already know that war is no good. So they try to refer to Iraq, or whatever. But Shakespeare chose this particular war, the Trojan war, for two good reasons. First, because it is a war about a woman, Helen of Troy, so it brings this subject of sex and betrayal right into the centre of the story«.

»And secondly, because it is a war of a particular kind, war as a kind of sport, with a large element of single combat. When we think of war, we think of someone flying an aeroplane and dropping a bomb, or firing a missile. We think of something in which most of the casualties are civilians - women, children, old people. This was not a war like that. It was more like a sport, full of the ridiculous and awful and nice and boyish behaviour of the male, that only at the very end becomes fatal. And you cannot work that out in a tragic way. It always remains in some way comic.«

Stein’s great passion for his work, in other words, is undiminished by the years, but it does raise the question of how this legendary director - once the boss of the mighty Berlin Schaubühne, and originator in the 1970s of its great experiment in the democratic governance of a huge producing theatre - organises his creative life today, with his home base in Italy, and his work spread across the theatres and opera houses of Europe.

»Well, I am a freelance director, and I have to say that this is for me a major disaster, that Brian McMaster is leaving the Edinburgh Festival. A great work-giver is going away, and I don't know what will happen to my theatre directing now. I often direct opera. Yes, it is beautiful and wonderful, it is much more established, they have much more money. But in the end, I am a theatre director, and the world of theatre is much more hand-to-mouth. Do I miss having my own theatre, my own company? Well, sometimes. The power, the feeling of having my own pile of money, the ability to do things exactly as I would like - that I miss. But I think running a building, and a company like the Schaubühne - you can only do it at a certain age, perhaps when you are 40. When you get older, you become too fixed in some way, you can’t mould yourself to the other people. The more you become yourself, the more difficult it is to be in a collective.«

»So do I think about the audience, when I am working? No, not really. I didn't even work that way back in the 1970s. I think you can only work that way if you are some ice-cold director of commercial musicals - and probably not even then, if you are a good one.«

»At the deepest level, I think about myself. I want to think and understand, and in that way, I am the audience for my work, here in the rehearsal room. So I am always telling the actors here« - and he refocuses intently on them, as they begin to return from their break - »that if they can make me understand this play, in a language that is not even my own, then the very worst fool in the audience should be able to understand, when we get to Edinburgh. And I hope that will be true.«

What the critics say:

David Yelland’s suavely plausible Ulysses delivers noble-sounding speeches for the most devious ends.

… a wonderfully funny performance from Julian Lewis Jones as a terminally stupid Ajax …

— The Daily Telegraph

… as lavishly meticulous a tribute to this great and disturbing play as British audiences are likely to see for decades to come.

… an astonishingly dark play, profoundly modern in its spirit of mocking subversions, and full of subtle resonances for our own time …

— The Scotsman

Additional info:

This epic production, directed by the brilliant Peter Stein, will go on from the Festival to the Royal Shakespeare Theatre in Stratford upon Avon as the Edinburgh International Festival’s contribution to the RSC’s year-long staging of all of Shakespeare’s work.